The first traffic rules – displacement and adaptation caused by the automobile

Around 1900, as was the case for millennia, the horse still dominated in the transport of people and loads. Only the utmost upper class could afford private cars. In 1914, people were already crying « Vienna is choking with traffic », although at that time there were only about 4,000 cars in Austria´s capital. Today, in Vienna alone, there are around 700,000 private vehicles.

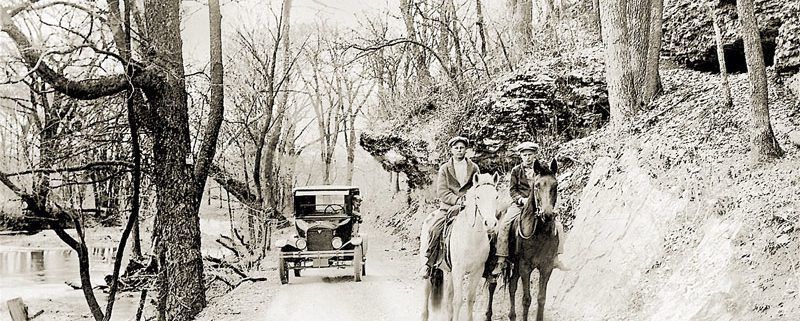

How did the formerly contemporary road users – pedestrians, cyclists, horse-drawn carriages and trams – deal with the introduction of automobiles on the roads? It was a « sensory shock » to the nose, ears and eyes, triggering many a feeling of powerlessness and anger at the omnipotence of the « driving machine gone wild ». The horses also suffered from the new noises on the street. Their shying was one of the biggest hurdles the automobile faced in becoming accepted in the early years.

Pedestrians felt displaced from the street – onto the sidewalks built especially for them. In 1911 the Viennese Police Directorate issued a walking order with the following instruction: « The city dweller must always keep in mind that the road’s lanes are primarily reserved for carriage traffic and that the sidewalk is intended for pedestrians. » The automobile appropriated the streets – unfortunately not without innumerable, often dramatic accidents. The « Reichspost » wrote of « automobile murders ». Nevertheless, the car won the adaptation and displacement process.

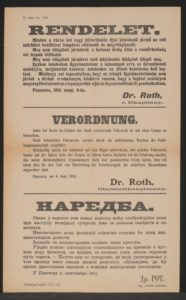

In contrast to the German Reich, until the Anschluss in 1938, Austria still had left-hand traffic, which had to be regulated. Initially, the rules that apply to traditional modes of transport were simply transferred to cars and motorcycles. Thus, the first speed restrictions were often based on the speed of the horse. The first regulations dated from around 1900. A heavily criticised ordinance from 1905 set the maximum speed on rural roads at 45 km/h, in built-up areas at 15 km/h – controlled by the police through their « own official perception ». The objectivity of this perception was soon in doubt and the first recording systems using photographs were developed.

Loud calls for traffic signage became apparent. During the « 1908 Paris Motor Show » four warning signs were decided upon (white on a blue background). These four symbols for ditch, curve, intersection and railroad crossing sufficed until 1926. Then another three followed; for unguarded level crossings, general dangers and for prohibited streets.

In Austria, the obligation to register and bear licence plates began only in 1905 with the decree from 27 September. Liability first came into force on 1 November, 1908 with the « Law on liability for damage arising from the operation of motor vehicles ». After that, drivers and owners were liable for any damage caused by the vehicle, including damage arising out of shying horses.

In 1910, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, as well as Germany, France, Great Britain, Spain, Italy, Monaco, and also Bulgaria and Russia, ratified an agreement establishing basic provisions on the registration of motor vehicles and drivers, the issue of international drivers licences, the affixing of licence plates, instructions on warning devices, special regulations concerning the operation of motorcycles, further traffic rules (meeting and overtaking of vehicles) and, ultimately, the establishment of signs on public roads. In Austria, a driving test became obligatory from 1912.

Quellen:

Seper, H.(1986): Österreichische Automobilgeschichte, Orac Verlag.

Technisches Museum Wien (2006): Spurwechsel. Wien lernt Auto fahren, Christian Brandstätter Verlag.

Austria Forum, Geschichte des Autos

Geschichte der Straße Fernverkehrssicherheit

Bildnachweis:

Bild 1: Wien 20, Wallensteinplatz (um 1910) © ÖNB, 69.547A (B)

Bild 2: Wien 1, Graben (1913), © ÖNB & Lichtbildstelle, L 27096 – B

Bild 3: Mehrsprachige Verordnung, Beleuchtung von Fuhrwerken & Linksfahrgebot (1914) ÖNB, KS 16213757